The Challenge

The client’s internal support portal was severely underperforming. Employees frustrated with the portal’s UX were abandoning the official workflow and resorting to backchannel support (calls, direct messages, personal emails), which bypassed the system. This work-around behavior skewed support analytics, slowed down issue resolution, and undermined trust in the portal. The portal served around 40,000 employees, so these inefficiencies created significant workload for support teams.

Stakeholders initially assumed the fault lay with “lazy” users not following procedure. Our original assignment was to build a virtual agent to funnel users back into the system. However, this assumption felt overly simplistic, and it risked masking deeper design failures. We suspected that users weren’t ignoring the portal out of laziness, but because the portal was failing them. The key challenge became diagnosing what about the current experience drove users away, before jumping to a solution.

Research & Insights

Reframing the Problem:

I led stakeholders through discussions to challenge the “users are lazy” narrative. We explored how apparent user “resistance” often signals unmet needs or cognitive friction. By explaining relevant psychology and usability principles, I won support to investigate root causes rather than immediately implement a chatbot. Stakeholders agreed to let our team step back and define the real problem through research.

Mixed-Methods Research:

We used multiple research approaches to uncover why employees avoided the portal and where the experience was breaking down:

Conducted in-depth interviews with real employees (20+ users) to hear their experiences. These highlighted pain points around lack of trust, previous failed attempts, and unclear navigation. One user explained, “I tried going through the proper process, but at the end of the day I still had to call someone.” This sentiment was common: people had lost faith that the portal would actually help them.

Polled a broad user base (≈300 respondents) and found consistent dissatisfaction with content findability and the usefulness of search results. Users often felt information was “there but impossible to find.”

Analysis of portal usage data found high bounce rates along with revealing that over 70% of users conducted repeated search queries (failure loops) in key flows. Many users would start in the portal but give up after hitting dead ends, then turn to backchannels for help.

Led an expert evaluation of the portal’s UI and architecture. We discovered that navigation and labeling didn’t match users’ mental models. Support content was scattered across dozens of sections with inconsistent terminology, leading to confusion and misdirection.

Key Problems Identified:

Synthesizing the research revealed several core UX problems with the legacy support portal:

The portal had become a dumping ground for content. The taxonomy and information architecture were convoluted, containing nearly 500 nested categories with overlapping or unclear labels.

The search interface was unintuitive; selecting a filter would hide other search criteria, and many sections had similar names. Users often couldn’t tell where they were now or where to go next.

The support pages lacked visual hierarchy and prioritization. Important help articles and FAQs were buried under irrelevant links and corporate jargon, accompanied by decorative images lacking value.

These issues had eroded user trust in the system. Employees weren’t bypassing the portal because they wanted to; they did it because prior attempts to self-serve had failed them. Our research made it clear that fixing these underlying UX problems was the key to reducing support workload, rather than simply adding a virtual agent on top of a broken foundation.

Design Solutions & Execution

Solutions Overview

With a solid understanding of the problems, our team proposed a comprehensive redesign to address the portal’s shortcomings. We focused on solutions that directly tackled each pain point. To implement these fixes methodically, I developed a phased roadmap with the client:

- Update content taxonomy

- Rebuild support content information architecture

- Re-map all support content

- Define governance procedures and content lifecycle

- Optimize search functionality

- Relaunch virtual agent

- Map end-to-end support delivery across channels

- Streamline backend flows

- Redesign front-end UX

Content Taxonomy & Information Architecture Overhaul

We began with the architecture. Our team performed a comprehensive content audit of the support portal, cataloguing nearly 500 taxonomical categories. Using Mural, we affinity-mapped related topics to spot redundant or illogical groupings. It became clear that many categories overlapped or were labeled in inconsistent ways, undermining both navigation and search.

I led a redesign of the information architecture to consolidate and clarify the taxonomy. We organized content into a leaner hierarchy of clearly named categories based on how users naturally think about their problems. To validate the new structure, we ran multiple rounds of tree testing via Optimal Workshop with real users. Over three iterations with 65 total participants, we fine-tuned the labels and grouping. Each round showed improvement, with misclassification rates dropping by over 30% with each iteration as the taxonomy became more aligned with user expectations.

The final taxonomy was not only user-friendly, but also compatible with the client’s ServiceNow platform constraints. We delivered a detailed information architecture blueprint to the client’s Knowledge Management team to implement the new structure in the portal’s backend.

Portal Interface Redesign

With the content organized, we turned to the front-end UI/UX design of the portal. Our goal was to make self-service the path of least resistance for employees. We mapped out new user flows based on common support tasks, ensuring the most sought-after resources were easy to find either by browsing or searching. After sketching solutions, we iterated quickly through low-fidelity wireframes to test layout ideas, then progressed to high-fidelity interactive prototypes for more in-depth usability tests.

The new portal design focused on clarity, simplicity, and guiding users to help resources quickly. Key improvements included:

A prominent search bar on the homepage, encouraging users to search in their own words with immediate, relevant results.

Streamlined navigation with a concise menu of top-level architectural categories based on the new taxonomy and visible pathways to subtopics.

Quick-access content sections using non-visual themes along with color and icon associations for the most common support content.

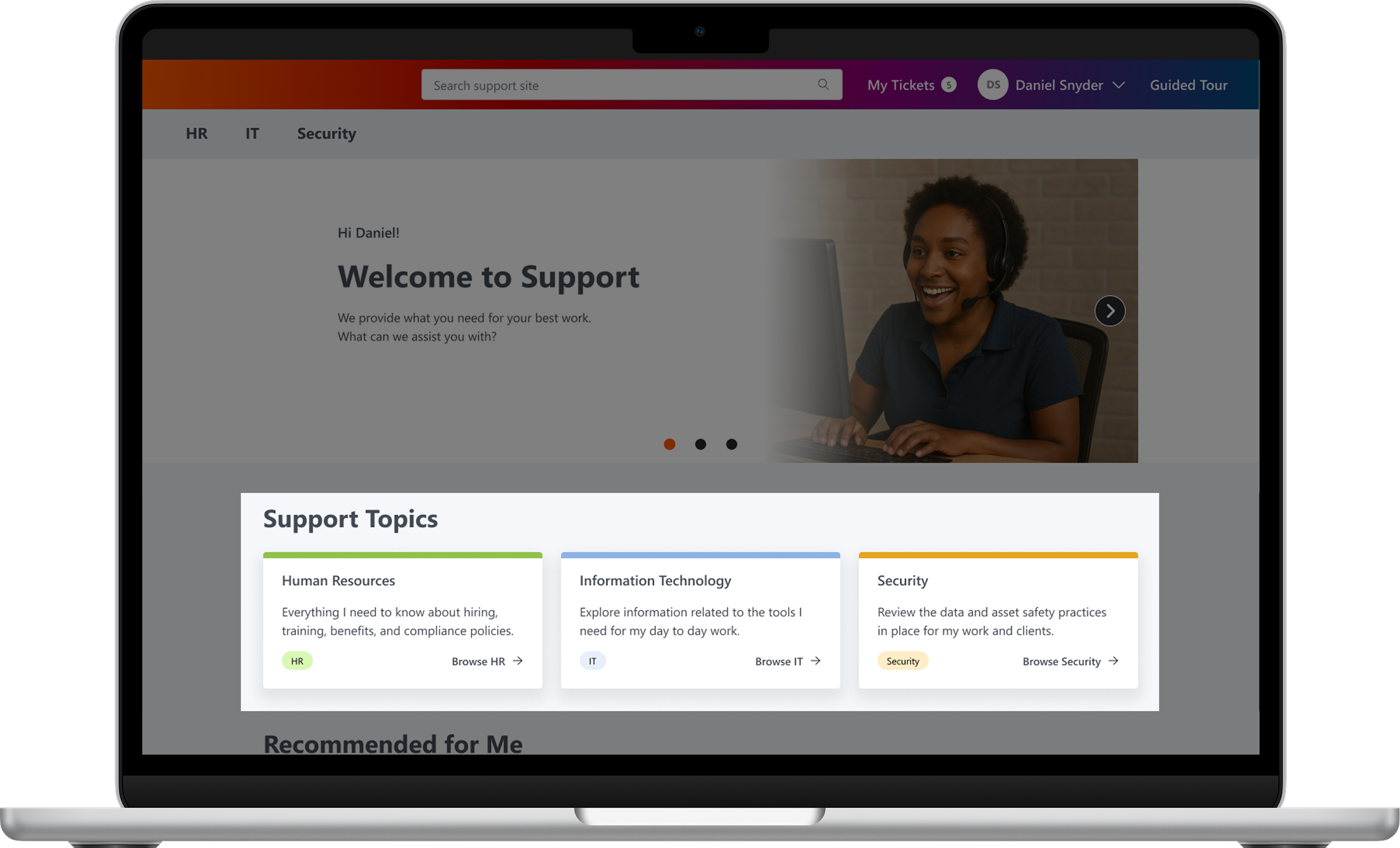

Figure 1: Final design for the enterprise support portal interface, focused on improving self-service outcomes. Features include a simplified layout, high-contrast accessibility enhancements, categorized quick-access buttons, and recommended content all built on a reorganized content taxonomy.

Other improvements included a cleaner content layout for support articles and improved visual design for accessibility. We introduced clear headings, accordions for organizing information, and removed distracting imagery. High-value content like recommended knowledge base categories or popular related resources were now highlighted prominently on the main page. Visual design now made use of a high-contrast, uncluttered interface with readable fonts and consistent styling, making it easier for all employees to use.

These design changes directly addressed the earlier pain points: users now had a clear starting point (search or top categories) and could actually find what they needed without wading through irrelevant links. The portal’s look and feel also reinforced credibility, helping to rebuild trust that “yes, the answer is here.”

Navigating Implementation Challenges

Early feedback on our prototypes was very positive, but we hit some bumps translating designs to production. Partway through development, the engineering team raised concerns that some of our previously approved solutions were too complex to build within the project constraints. This disconnect led to delays and threatened to erode team trust.

To get us back on track, I took initiative to adjust our collaboration process:

- I introduced mid-fidelity technical review checkpoints so that engineers could vet design concepts for feasibility much earlier, before we invested too much in high-fidelity details.

- We embedded platform technical constraints and guidelines into our Figma designs and documentation. This meant developers had full context (e.g. ServiceNow component limitations) while implementing, reducing surprises.

- I facilitated cross-functional retrospectives and workshops to improve communication. These open forums allowed the team to voice concerns, clarify misunderstandings, and collectively brainstorm simpler alternatives when needed.

By proactively addressing these execution issues, we rebuilt confidence between design and engineering. The final designs were delivered as a fully feasible, testable solution that met our user experience goals without breaking the build process.